Subatomic particle

In physics, a subatomic particle is a particle smaller than an atom. According to the Standard Model of particle physics, a subatomic particle can be either a composite particle, which is composed of other particles (for example, a proton, neutron, or meson), or an elementary particle, which is not composed of other particles (for example, an electron, photon, or muon). Particle physics and nuclear physics study these particles and how they interact.

Experiments show that light could behave like a stream of particles (called photons) as well as exhibiting wave-like properties. This led to the concept of wave–particle duality to reflect that quantum-scale particles behave both like particles and like waves; they are sometimes called wavicles to reflect this.

Another concept, the uncertainty principle, states that some of their properties taken together, such as their simultaneous position and momentum, cannot be measured exactly. The wave–particle duality has been shown to apply not only to photons but to more massive particles as well.

Interactions of particles in the framework of quantum field theory are understood as creation and annihilation of quanta of corresponding fundamental interactions. This blends particle physics with field theory.

Even among particle physicists, the exact definition of a particle has diverse descriptions. These professional attempts at the definition of a particle include:

- A particle is a collapsed wave function

- A particle is a quantum excitation of a field

- A particle is an irreducible representation of the Poincaré group

- A particle is an observed thing

Classification

By composition

Subatomic particles are either "elementary", i.e. not made of multiple other particles, or "composite" and made of more than one elementary particle bound together.

The elementary particles of the Standard Model are:

- Six "flavors" of quarks: up, down, strange, charm, bottom, and top;

- Six types of leptons: electron, electron neutrino, muon, muon neutrino, tau, tau neutrino;

- Twelve gauge bosons (force carriers): the photon of electromagnetism, the three W and Z bosons of the weak force, and the eight gluons of the strong force;

- The Higgs boson.

All of these have now been discovered by experiments, with the latest being the top quark (1995), tau neutrino (2000), and Higgs boson (2012).

Various extensions of the Standard Model predict the existence of an elementary graviton particle and many other elementary particles, but none have been discovered as of 2021.

Hadrons

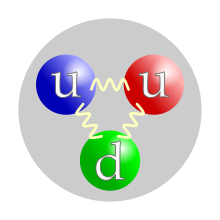

The word hadron comes from Greek and was introduced in 1962 by Lev Okun. Nearly all composite particles contain multiple quarks (and/or antiquarks) bound together by gluons (with a few exceptions with no quarks, such as positronium and muonium). Those containing few (≤ 5) quarks (including antiquarks) are called hadrons. Due to a property known as color confinement, quarks are never found singly but always occur in hadrons containing multiple quarks. The hadrons are divided by number of quarks (including antiquarks) into the baryons containing an odd number of quarks (almost always 3), of which the proton and neutron (the two nucleons) are by far the best known; and the mesons containing an even number of quarks (almost always 2, one quark and one antiquark), of which the pions and kaons are the best known.

Except for the proton and neutron, all other hadrons are unstable and decay into other particles in microseconds or less. A proton is made of two up quarks and one down quark, while the neutron is made of two down quarks and one up quark. These commonly bind together into an atomic nucleus, e.g. a helium-4 nucleus is composed of two protons and two neutrons. Most hadrons do not live long enough to bind into nucleus-like composites; those that do (other than the proton and neutron) form exotic nuclei.

By statistics

Any subatomic particle, like any particle in the three-dimensional space that obeys the laws of quantum mechanics, can be either a boson (with integer spin) or a fermion (with odd half-integer spin).

In the Standard Model, all the elementary fermions have spin 1/2, and are divided into the quarks which carry color charge and therefore feel the strong interaction, and the leptons which do not. The elementary bosons comprise the gauge bosons (photon, W and Z, gluons) with spin 1, while the Higgs boson is the only elementary particle with spin zero.

The hypothetical graviton is required theoretically to have spin 2, but is not part of the Standard Model. Some extensions such as supersymmetry predict additional elementary particles with spin 3/2, but none have been discovered as of 2021.

Due to the laws for spin of composite particles, the baryons (3 quarks) have spin either 1/2 or 3/2 and are therefore fermions; the mesons (2 quarks) have integer spin of either 0 or 1 and are therefore bosons.

By mass

In special relativity, the energy of a particle at rest equals its mass times the speed of light squared, E = mc2. That is, mass can be expressed in terms of energy and vice versa. If a particle has a frame of reference in which it lies at rest, then it has a positive rest mass and is referred to as massive.

All composite particles are massive. Baryons (meaning "heavy") tend to have greater mass than mesons (meaning "intermediate"), which in turn tend to be heavier than leptons (meaning "lightweight"), but the heaviest lepton (the tau particle) is heavier than the two lightest flavours of baryons (nucleons). It is also certain that any particle with an electric charge is massive.

When originally defined in the 1950s, the terms baryons, mesons and leptons referred to masses; however, after the quark model became accepted in the 1970s, it was recognised that baryons are composites of three quarks, mesons are composites of one quark and one antiquark, while leptons are elementary and are defined as the elementary fermions with no color charge.

All massless particles (particles whose invariant mass is zero) are elementary. These include the photon and gluon, although the latter cannot be isolated.

By decay

≤Other properties

All observable subatomic particles have their electric charge an integer multiple of the elementary charge. The Standard Model's quarks have "non-integer" electric charges, namely, multiple of 13 e, but quarks (and other combinations with non-integer electric charge) cannot be isolated due to color confinement. For baryons, mesons, and their antiparticles the constituent quarks' charges sum up to an integer multiple of e.

Through the work of Albert Einstein, Satyendra Nath Bose, Louis de Broglie, and many others, current scientific theory holds that all particles also have a wave nature. This has been verified not only for elementary particles but also for compound particles like atoms and even molecules. In fact, according to traditional formulations of non-relativistic quantum mechanics, wave–particle duality applies to all objects, even macroscopic ones; although the wave properties of macroscopic objects cannot be detected due to their small wavelengths.

Interactions between particles have been scrutinized for many centuries, and a few simple laws underpin how particles behave in collisions and interactions. The most fundamental of these are the laws of conservation of energy and conservation of momentum, which let us make calculations of particle interactions on scales of magnitude that range from stars to quarks. These are the prerequisite basics of Newtonian mechanics, a series of statements and equations in Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, originally published in 1687.

Dividing an atom

The negatively charged electron has a mass of about 11836 of that of a hydrogen atom. The remainder of the hydrogen atom's mass comes from the positively charged proton. The atomic number of an element is the number of protons in its nucleus. Neutrons are neutral particles having a mass slightly greater than that of the proton. Different isotopes of the same element contain the same number of protons but differing numbers of neutrons. The mass number of an isotope is the total number of nucleons (neutrons and protons collectively).

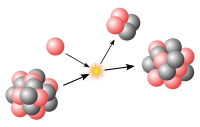

Chemistry concerns itself with how electron sharing binds atoms into structures such as crystals and molecules. The subatomic particles considered important in the understanding of chemistry are the electron, the proton, and the neutron. Nuclear physics deals with how protons and neutrons arrange themselves in nuclei. The study of subatomic particles, atoms and molecules, and their structure and interactions, requires quantum mechanics. Analyzing processes that change the numbers and types of particles requires quantum field theory. The study of subatomic particles per se is called particle physics. The term high-energy physics is nearly synonymous to "particle physics" since creation of particles requires high energies: it occurs only as a result of cosmic rays, or in particle accelerators. Particle phenomenology systematizes the knowledge about subatomic particles obtained from these experiments.

History

The term "subatomic particle" is largely a retronym of the 1960s, used to distinguish a large number of baryons and mesons (which comprise hadrons) from particles that are now thought to be truly elementary. Before that hadrons were usually classified as "elementary" because their composition was unknown.

A list of important discoveries follows:

No comments:

Post a Comment